25-Sep-2020

The Mar-2017 cover story of Wired magazine (UK) was catastrophic / existential risks (one of their Top 10 risks was global pandemic, so Wired has certainly delivered in the future-forecasting department). It featured, among other esteemed research centres (such as Cambridge University’s Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence or Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute), Centre for the Study of Existential Risk (like LCFI, also based in Cambridge).

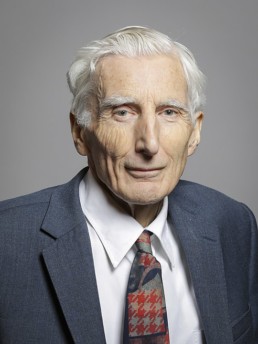

CSER was co-founded by Lord Martin Rees, who is one person I can think of to genuinely deserve this kind of title (I’m otherwise rather Leftist in my views and I’m all for merit-based titles and distinctions – and *only* those). Martin Rees is practically a household name in the UK (I think he’s UK’s second most recognisable scientist after Sir David Attenborough), where he is the Astronomer Royal, the former Master of Trinity College in Cambridge, and the former President of the Royal Society (to name but a few). Lord Rees has for many years been an indefatigable science communicator, and his passion and enthusiasm for science are better witnessed than described. Speaking from personal observation, he also comes across as an exceptional individual on a personal level.

Fun fact: among his too-many-to-list honours and awards one will not find the Nobel Prize, which is… disappointing (not as regards Lord Rees, but as regards the Nobel Prize committee). One will however find a far lesser-know Order of Merit (OM). The number of living Nobel Prize recipients is not capped and stands at about 120 worldwide. By comparison, there can be only 24 living OMs at any one time. Though lesser known, the OM is widely regarded as one of the most prestigious honours in the world.

By Roger Harris – https://members-api.parliament.uk/api/Members/3751/Portrait?cropType=ThreeFourGallery: https://members.parliament.uk/member/3751/portrait, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=86636167

Lord Rees has authored hundreds of academic articles and a number of books. His most recent book is On the Future, published in 2018. In Sep-2020 Lord Rees delivered a lecture on existential risk as part of a larger event titled “Future pandemics” held at the Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences in Cambridge. The lecture was very much thematically aligned with his latest book, but it was far from the typical “book launch / promo / tie-in” presentation I have attended more than once in the past. The depth, breadth, vision, and intellectual audacity of the lecture were nothing short of mind-blowing – it was akin to a full-time postgraduate course compressed into one hour. Interestingly, the lecture was very “open-ended” in terms of the many technologies, threats, and visions Lord Rees has covered. Oftentimes similar lectures focus on a specific vision or prediction and try to sell it to the audience wholesale; with Lord Rees it was more of a roulette of possible events and outcomes: some of them terrifying, some of them exciting, and some of them unlikely.

The lecture started with the familiar trends of population growth and shifting “demographic power” from the West to Asia and Africa (the latter likely to experience the most pronounced population growth throughout 21st century), followed by the climate emergency. On the climate topic Lord Rees stressed the urgency for green energy sources, but he seemed a bit more realistic than many in terms of attainability of that goal on a mass scale. Consequently, he introduced and discussed Plan B, i.e. geoengineering. If “geoengineering” sounds somewhat familiar, it is likely because of a high-profile planned Harvard University experiment publicised by the MIT Tech Review . . . which was subsequently indefinitely halted. I was personally very supportive of the Harvard experiment as one possible bridge between the targets of the Paris Accord and the reality of the climate situation on the ground. Lord Rees then discussed the threat of biotechnology and casual biohacking / bioengineering, citing as an example a Dutch experiment of weaponizing the flu virus to make it more virulent. The lecture really got into gear from then onwards, as Lord Rees began pondering the future of evolution itself (the evolution of evolution so to speak), where traditional Darwinian evolution may be replaced or complemented (and certainly accelerated by orders of magnitude) by man-powered genetic engineering (CRISPR-Cas9 and alike) and / or ultimate evolution of intelligent life into synthetic forms, which leads to fundamental and existential questions of what will be the future definition of life, intelligence, or personal identity. [N.B. These discussions are being had on many levels by many of the finest (and less-than-finest) minds of our time. I am not competent to provide even a cursory list of resources, but I can offer two of my personal favourites from the realm of sci-fi: the late, great Polish sci-fi visionary Stanislaw Lem humorously tackled the topic of bioengineering in Star Diaries (Voyage Twenty-One) while Greg Egan has taken on the topic of (post)human evolution in the amazing short story “Wang’s carpets”, further expanded into a full-length novel Diaspora.]

From life on Earth Lord Rees moves on to life outside Earth, disagreeing with the idea of other planets being humanity’s “Plan B” and touching (but not expanding) on the topic of extraterrestrial life. The truly cosmic in scope a lecture ended with a much more down-to-Earth call for political action as well as (interestingly) action from religions and religious leaders on the environmental front.