Wed 06-May-2020

I don’t watch TV (I’m using the term loosely and inclusively, i.e. including Netflixes and Amazon Prime Videos of this world) much, and when I do, I’m usually so tired that it’s either Family Guy, or an umpteenth rerun of one of my go-to masterpieces: Aliens, The Matrix, The Matrix Reloaded, Alien: Resurrection, Resident Evil, Terminator 2, Total Recall, Contagion, Predator, Basic Instinct, Batman, Batman Returns, Dark Knight Rising – I think you get the idea. I try to make an effort to watch the more ambitious fare, but the truth is that with full-time work, studies, FOMO, and casual depression there isn’t always enough glucose in the brain to concentrate on something new and challenging. When there is, there is sometimes a great prize, a grand prix (most recently: Lee Chang-dong’s Burning… Jesus Marimba, what a movie…!). Last weekend, spurred by word of mouth, I watched Alex Garland’s (of Ex Machina and Annihilation fame) latest creation Devs.

While Dev’s production budget is impossible to come by on the Internet, I’m guessing low- to mid-eight figure (my working guess is USD 20m – 30m range; I’d be heavily surprised it were a single penny over USD 50m). The show isn’t as visually blockbusting as Westworld (and let’s be clear: the two will forever be mentioned and compared on one breath, for a number of reasons: artistic ambitions, philosophical under(or over-)tones, auteur aesthetic, focus on cutting-edge technologies, and airing at the exact same time [Devs vs. Westworld season 3] – lastly, a painful lack of any humour or irony, as both shows take themselves oh so very seriously).

Entertainment – quality entertainment – Is often revealing a lot about the collective mindset at the time of the release (aka zeitgeist). There are, of course exceptions: masterpieces such as 2001: A Space Odyssey or Solaris (Tarkovsky’s, not Soderbergh’s!) didn’t provoke fears of sentient AI back in the 1960’s or strange alien worlds in the 1970’s respectively; they were visionary works either untethered from the everyday experience, or decades ahead of their time. In recent years we could see how transhumanism became mainstream in (wildly uneven) productions such as Transcendence (can you spot the cameo of Wired magazine in one of the scenes? It’s the best acting performance of the entire movie), Limitless (which made 6x its budget), or Lucy (which made 11x its budget) – not to mention genre-defining classics such as Ghost in the Shell (The 1995 one! Not the Scarlett Johansson trainwreck) or the Matrix trilogy. Transhumanism has enormous cinematic potential, which has been nowhere near fully utilised; it has, however, had some less-than-ideal timing, because we still haven’t advanced anything like Lucy’s CPH4 or Limitless’ NZT-48 on the nootropics side, nor brain-computer interfaces (BCI’s) from the Matrix, cortical stacks from Altered Carbon, or cyberbrains and synthetic “shells” from Ghost in the Shell. With transhumanism still awaiting its breakthroughs, AI provided more than was required to fully capture mass imagination in recent years (Ex Machina, Westworld, Her, Humans). Devs are going a step further: to the fascinating world of quantum computing.

It’s a challenge to clearly define what genre Devs actually belongs to. It’s not science-fiction nor a technothriller, because technology – while absolutely central to the story – is not the story itself (unlike, for example, HAL in 2001). It’s not a murder mystery nor a crime thriller, because we see the murder in the first 15 minutes of the first episode, we see who killed – alas, we don’t know why they killed. The entire storyline of the series is all about understanding this seemingly absurd, unnerving “why”. The series is closest to philosophical and existential drama. It doesn’t feature red herrings or parallel timelines, and all characters, props, and plot devices appear for a reason, which makes for a refreshing break from oft-overengineered narratives of modern-day dramas. It is as close to minimalist as possible for an FX production. It is also highly stylised, beautiful, and high on artistic and technical merits.

Cinematography in Dev is an absolute delight; a technical and artistic tour de force (if Devs doesn’t get a clean sweep of the technical and art direction Emmy’s and Golden Globes, that’s it, I’m giving up on mankind). The cinematography is crisp and dreamlike at the same time, it has an incredible hyperreal feel. It is also rife in references – and as is often the case with not-so-overt ones, one wonders “is this an actual reference, or am I just inventing one?”. Night-time aerial sequences of LA seem like a clear reference to (original) Blade Runner’s visionary imagery, while daytime sequences share a degree of Sun saturation with Dredd (an underrated masterpiece Alex Garland wrote and executive-produced). The Devs unit design is homage to Vincenzo Natali’s Cube, there’s no way it’s accidental, while its brighter-than-sun lighting evokes 2007 Sunshine (written by Garland). The technical quality of the cinematography shines brightest in razor-sharp, vivid, saturated night shots – which makes one contemplate the incredible technological leap of the past 2 decades; just see one of big-budget Hollywood productions night shots from late 90’s (off the top of my head: Interview with the Vampire) to see how the technology has progressed.

Music is at times perhaps too arthouse, but it is clearly a part of the artistic vision, it’s a standout character, not a backdrop – and most of the time, it works oh so well. Once again, one can’t help but draw comparisons with Vangelis’ groundbreaking Blade Runner score, or the equally groundbreaking selection of music for 2001. On the intelligent ambient electronica side, Cristobal Tapia de Veer arresting score for Channel 4’s underrated masterpiece Utopia or Cliff Martinez’s score for Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion come to mind. Westworld’s soundtrack by Ramin Djawadi is nothing to sneeze at (especially the beautifully bittersweet Sweetwater), but it’s clearly illustration music. Devs seem closer to Brian Retizell’s avant-garde experimentations on Hannibal or subliminal ambient background to David Lynch’s 2017 Twin Peaks revival (sound-designed by David Lynch himself).

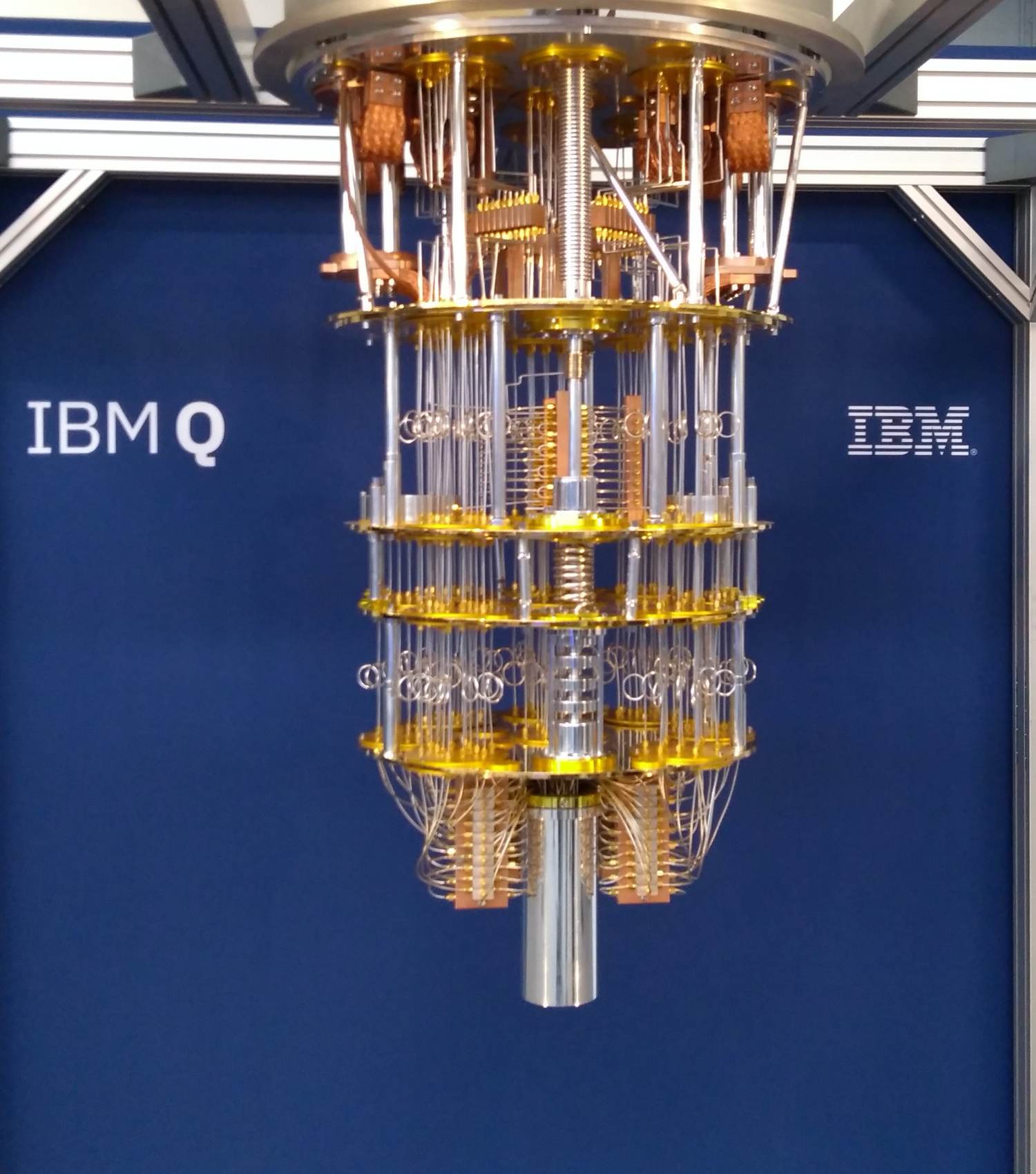

Art direction is interesting, though not at par with music or cinematography. The LA apartments of the protagonists are pretty basic (although we get the not-so-subtle message “even these basic apartments are nowadays affordable for the technocratic elite only”). The Devs’ “floating cube” is, by contrast, intentionally (?) over-the-top, while the Amaya statue towering over the campus is quite creepy, likely meant as a warning against not letting go. The way New York City was the fifth character on Sex and the City, in Devs it’s the quantum computer – which is either a carbon copy of IBM Q System One (I’ve seen it up close – a mock-up, of course, not the real, super-cooled thing), or it is actually the exact mock-up I saw (the one in Devs has some moving parts though… I’m not sure the IBM / D-Wave / Rigetti systems have any of those…). To a regular viewer it may look completely and utterly over the top, like an elongated baroque candelabra put on the floor – the weird thing is, this is exactly what a modern-day quantum computer looks like; there’s no OTT here – that’s scientific accuracy.

Art direction is interesting, though not at par with music or cinematography. The LA apartments of the protagonists are pretty basic (although we get the not-so-subtle message “even these basic apartments are nowadays affordable for the technocratic elite only”). The Devs’ “floating cube” is, by contrast, intentionally (?) over-the-top, while the Amaya statue towering over the campus is quite creepy, likely meant as a warning against not letting go. The way New York City was the fifth character on Sex and the City, in Devs it’s the quantum computer – which is either a carbon copy of IBM Q System One (I’ve seen it up close – a mock-up, of course, not the real, super-cooled thing), or it is actually the exact mock-up I saw (the one in Devs has some moving parts though… I’m not sure the IBM / D-Wave / Rigetti systems have any of those…). To a regular viewer it may look completely and utterly over the top, like an elongated baroque candelabra put on the floor – the weird thing is, this is exactly what a modern-day quantum computer looks like; there’s no OTT here – that’s scientific accuracy.

It doesn’t often happen that all elements click into place to create perfection (examples in recent years: American Horror Story season 1; Hannibal; Killing Eve, Fleabag; Twin Peaks: the Return), and unfortunately Devs aren’t quite so lucky. All its artistic and philosophical heft is undermined – painfully! – by terribly miscast leads. Some TV shows (again, using the term loosely) are cast pitch-perfect, the cast makes these shows (cases in point: Killing Eve; Hannibal; seasons 1, 2, and 5 of American Horror Story; Pose; characters of Dolores and Maeve in Westworld; Olive Kitteridge; Transparent). Given the budgets that go into modern series production, and the enormous stakes (as the shows become flagships for their platforms / networks and fight to compete in increasingly saturated marketplace) casting can make or break a show. The lead cast of Devs doesn’t quite break the show, but it’s not for the lack of trying.

Sonoya Mizuno as Lily is. a. disaster. She’s got an intriguing, androgynous appeal, but – looking at a broad and subjective spectrum of similarly intriguing actresses – she doesn’t have the sex-appeal of Tao Okamoto or Ève Salvail, the talent of Rinko Kikuchi or Saoirse Ronan, nor the charisma of Carrie-Ann Moss or Chiaki Kuriyama. We know that Alex Garland can direct its actors well (after all, Ex Machina propelled Alicia Vikander to Hollywood’s A-list; she got an Oscar a year later for The Danish Girl), so the fault is likely with Mizuno. She carries Lily with the depth of an emo teenager; her acting is flat, her emotional range is limited. I felt like crying during her crying scene, but it wasn’t tears of empathy – it was cringe-cry. Nick Offerman’s Forest takes the blank-stare dead eyes so far over the top that it’s at times almost comical. Karl Glusman – an otherwise talented actor – does Russian accent… poorly – and that’s his only contribution. Alison Pill also went over-the-top with the “brooding quantum physics genius”, doubling down on blank stare and mistaking flatness for depth – she simply isn’t convincing as a scientist. Relative newcomer Jin Ha as Jamie is the only casting bet that pays off (and just to be clear: one doesn’t need a cast of Hollywood A-listers to make a good series – just look at Succession). His character doesn’t get that much air time, but still comes across as a fully-fleshed character. He’s also refreshingly sensitive and vulnerable, which are not qualities we get to see in male protagonists very often yet. He’s nowhere near hypermasculine, he’s actually really slim-built, even slightly androgynous (androgyny is a major theme in Devs: Lily, Jamie, Lyndon – it almost seems like a message: “the intellectual / technocratic elite is above the archaic gender-binary”). Zach Grenier’s is the only other half-decent performance, with redeeming flashes of irony. No Emmy’s here. No Golden Globes.

Devs’ is a living proof that powerful vision is enough to create compelling, fascinating, binge-worthy TV. It does so without a plethora of international locations (I’m looking at you, Westworld!), an abundance of CGI (I’m still looking at you, Westworld), or elaborate purpose-built sets (my eyes still on you, Westworld). Devs has precisely one blockbusting scene (the motorway sequence with Lily and Kenton). By the very virtue of its location, it evokes Bullitt, otherwise, it is reminiscent of that motorway scene in Matrix Reloaded (obviously in a much more demure fashion – the Matrix Reloaded sequence was a stroke of cinematic genius, down to the Juno Reactor track).

As far as philosophy and technology are concerned… well, the latter is approached loosely… really loosely. It’s more of a mere notion of quantum computing than any actual science. It’s kind of the vaguest and loosest level of technological reference possible – but, judging by the reactions, it was enough to strike a chord. The reason may be two-fold: the artistic and entertainment merits of Devs, and perfect timing, as “quantum” becomes the hot new buzzword. Philosophy is more of a meditation and exploration – there are few (if any) answers or directions. It may, in fact, be one of the major strengths of Devs: it ponders and asks questions without fortune cookie-quality one-liner bits of wisdom (“There is ugliness in this world. Disarray. I choose to see beauty” – look me in the eye, Westworld…!). Westworld takes on sentience and consciousness; Devs takes on free will and determinism. It’s interesting (and impressive) how Devs gently manages to manoeuvre around the topic of religion and comes across as agnostic rather than explicitly atheistic.

Devs is a show one can describe as a “small masterpiece”. It’s slow-burning, low-key, with stunning aesthetics though no blockbusting qualities proper. The characters are not at all overtly sexy or sexual (in fact they come across somewhat asexual, even though we know they do, actually, have sex and enjoy it). There are no heists, explosions, or enormous amounts of money (money is approached a bit like sex in Devs – we know it exists, and in great amounts, but it’s almost a non-factor for the plot). One could say that not very much is happening in Devs altogether, and they wouldn’t necessarily be wrong. But somewhere between bold artistic vision, philosophical questions, stunning visuals, and outstanding music there is a true work of art: ambiguous, intriguing, thought-provoking, and truly beautiful. I’ll treasure it all the more knowing full-well how unlikely I am to see anything of remotely similar calibre anytime soon.

PS. Is it just me, or does it look like the scene of meeting Lily and Jamie was filmed on the non-existent ground floor of Exchange House in Primrose Street in London?