London Futurists: Adventures at the Frontier of Birth, Food, Sex & Death

Mon 13-Jul-2020

On Monday 13th of July 2020 I attended (virtually, of course) one of my favourite meetup series, David Wood’s London Futurists. The event was mostly focused around the key themes of Jenny Kleeman’s recent book (“Sex robots & vegan meat: Adventures at the Frontier of Birth, Food, Sex & Death”), with Kleeman herself featured as the keynote (but not the only) speaker.

Frankly, I think that addressing the future of all-that-really-counts-in-life in one book and one event is a somewhat over-ambitious task. Fortunately, the speakers didn’t attempt to present a comprehensive vision of mankind’s future according to themselves. Instead, they presented a series of concepts which are either in existence at present, or are extrapolated into the near future. This way each attendee could piece together their own vision of the future, which made for a much more thought-provoking and interesting experience than having a uniform vision laid out.

I paid limited attention to the part concerning vegan meat / meat alternatives / meat substitutes. I have a fairly complicated relationship with animal products as it is, a relationship that can be perfectly summed up in Ovid’s famous phrase “video meliora proboque, deteriora sequor” (“I see better things and I approve them, but I follow the worse things”). I *would like to* be vegan, but, frankly, I experience limited guilt eating chicken or fish. I eat pork in the form of ham on my sandwiches and in my scrambled eggs, so not that much. Milk and eggs are a challenge, as they are added as ingredients to *everything* (chief among them vegetable soup, milk chocolate [obvs], and cakes). I can live with guilty conscience, but I cannot live without vegetable soup, milk chocolate, or cake. I believe that the (not-so-) invisible hand of the market is driving food production quite aggressively towards veganism, and when I can switch with zero-to-little flavour sacrifice (even if it means paying a premium), I will do so. In any case, I think that vegan (or almost vegan) future is almost a done deal now; seeing vegan burger options at the likes of McDonald’s and KFC dispelled any doubts I may have had.

One thing that immediately comes to my mind when discussing meat-free alternatives to meat products is the acerbic hilarity brought on by the meat and dairy incumbents in the semantics department. Kleeman mentioned ongoing disputes over what exactly can correctly be referred to as “milk” or “meat”. I raise and check with US Egg Board (not making this up!) suing a vegan may start-up Just Mayo over… a misleading use of the term “mayo”. Feel free to Google it, it’s one of those stories where life beats fiction.

Sex robots are something I am relatively familiar with (in theory only! – I attended one or two presentations on the topic). On this one I am slightly unconvinced to be honest… I’m all for sex toys, but I think that when it comes to the full experience I couldn’t self-delude myself to the point of being able to… “engage” with a doll or a robot. I think that for those who do not have an intimate partner porn, camming, or sex workers are all much better options. That being said, technology might leap, and my views might change as I’m getting older… One observation made by the speakers really struck a chord with me: companion robots can get “weaponised” by commercial or political interests, influencing (effectively exploiting) their emotionally attached owners’ choices: from their pick of a shampoo brand to presidential elections. I can picture that happening in foreseeable future and upending the society. It will also be a legal minefield…

Anecdotes from the frontlines of birth and death have definitely rattled me the most. Apparently mankind is only a short time away from fully-functional external wombs, which has the potential to profoundly shake the foundations of the society.

The woman’s choice may no longer be between pregnancy and abortion. An unwanted healthy pregnancy could be transferred to an external womb, where it could gestate until birth. The ethical, moral, and legal implications of such option are staggering (in some countries this would be a choice; in others, where abortion is fully or largely prohibited, this could be enforced on pregnant women who would want to terminate the pregnancy). I think about abortion protests taking place all over Poland as we speak (and in countless cities with Polish diasporas outside Poland), I think about what far-right politicians are willing to do to women’s rights and bodies… and it’s chilling.

This doesn’t just concern unwanted pregnancies: what about expectant mothers with poor lifestyles (e.g. smokers)? Could they face forced extractions into a (healthier) artificial womb?

Lastly, this may become a lifestyle choice for women who do not want to carry their pregnancy. It is conceivable that standard pregnancy may at some point become a symbol of low status.

Finally, there’s death; still an inevitability (though, according to transhumanists, not for much longer). Frankly, I expected the wildest visions to concern sex, but I was badly mistaken: nothing beats death (so to speak). The speakers presented a logical, coherent, (and horrifying) prospect of death as an economic choice in modern, rapidly ageing societies. A terminally ill person could be presented by the state with a choice: to live out their life at a huge cost to the state, or go for immediate, painless euthanasia whereby a percentage of the saved amount (e.g. 25%) would be bequeathed to the person’s family. Similar choice could be offered to people serving long sentences in prison.

State-sponsored euthanasia may seem too dystopian (Logan’s Run-style), but what about taking one’s death into one’s own hands (particularly in light of severe physical or mental health issues)? Suicide has been a part of mankind’s experience forever and yet it remains highly stigmatised among many cultures and religions to this day. Euthanasia remains even more controversial, and is allowed only in handful of countries (Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Canada, Australia, and Colombia if I’m not mistaken). Every now and then a person who wishes to die but is unable to do so due to severe incapacitation makes headlines with their court case or attempts to take their own life. In the near future innovative solutions like Sarco euthanasia device may allow more people to end their lives when they so choose, in an (allegedly) painless way, thus effectively “democratising” suicide / euthanasia.

The visions presented in the London Futurists’ event range from lifestyle-altering (vegan alternatives to meat and dairy; sex robots) to profound (companion robots; artificial wombs; euthanasia). Some of them are already here, some of them are not. We can’t know for sure which ones will be mass-adopted, and which ones will be rejected by the society – we will only know that in time. It is also more than likely that there will be some inventions at the frontier of birth, food, sex, and death that even futurists can’t foresee. The best we can do is remain open-minded (perhaps cautiously hopeful) regarding the future and take little for granted.

“Devs” series review

Wed 06-May-2020

I don’t watch TV (I’m using the term loosely and inclusively, i.e. including Netflixes and Amazon Prime Videos of this world) much, and when I do, I’m usually so tired that it’s either Family Guy, or an umpteenth rerun of one of my go-to masterpieces: Aliens, The Matrix, The Matrix Reloaded, Alien: Resurrection, Resident Evil, Terminator 2, Total Recall, Contagion, Predator, Basic Instinct, Batman, Batman Returns, Dark Knight Rising – I think you get the idea. I try to make an effort to watch the more ambitious fare, but the truth is that with full-time work, studies, FOMO, and casual depression there isn’t always enough glucose in the brain to concentrate on something new and challenging. When there is, there is sometimes a great prize, a grand prix (most recently: Lee Chang-dong’s Burning… Jesus Marimba, what a movie…!). Last weekend, spurred by word of mouth, I watched Alex Garland’s (of Ex Machina and Annihilation fame) latest creation Devs.

While Dev’s production budget is impossible to come by on the Internet, I’m guessing low- to mid-eight figure (my working guess is USD 20m – 30m range; I’d be heavily surprised it were a single penny over USD 50m). The show isn’t as visually blockbusting as Westworld (and let’s be clear: the two will forever be mentioned and compared on one breath, for a number of reasons: artistic ambitions, philosophical under(or over-)tones, auteur aesthetic, focus on cutting-edge technologies, and airing at the exact same time [Devs vs. Westworld season 3] – lastly, a painful lack of any humour or irony, as both shows take themselves oh so very seriously).

Entertainment – quality entertainment – Is often revealing a lot about the collective mindset at the time of the release (aka zeitgeist). There are, of course exceptions: masterpieces such as 2001: A Space Odyssey or Solaris (Tarkovsky’s, not Soderbergh’s!) didn’t provoke fears of sentient AI back in the 1960’s or strange alien worlds in the 1970’s respectively; they were visionary works either untethered from the everyday experience, or decades ahead of their time. In recent years we could see how transhumanism became mainstream in (wildly uneven) productions such as Transcendence (can you spot the cameo of Wired magazine in one of the scenes? It’s the best acting performance of the entire movie), Limitless (which made 6x its budget), or Lucy (which made 11x its budget) – not to mention genre-defining classics such as Ghost in the Shell (The 1995 one! Not the Scarlett Johansson trainwreck) or the Matrix trilogy. Transhumanism has enormous cinematic potential, which has been nowhere near fully utilised; it has, however, had some less-than-ideal timing, because we still haven’t advanced anything like Lucy’s CPH4 or Limitless’ NZT-48 on the nootropics side, nor brain-computer interfaces (BCI’s) from the Matrix, cortical stacks from Altered Carbon, or cyberbrains and synthetic “shells” from Ghost in the Shell. With transhumanism still awaiting its breakthroughs, AI provided more than was required to fully capture mass imagination in recent years (Ex Machina, Westworld, Her, Humans). Devs are going a step further: to the fascinating world of quantum computing.

It’s a challenge to clearly define what genre Devs actually belongs to. It’s not science-fiction nor a technothriller, because technology – while absolutely central to the story – is not the story itself (unlike, for example, HAL in 2001). It’s not a murder mystery nor a crime thriller, because we see the murder in the first 15 minutes of the first episode, we see who killed – alas, we don’t know why they killed. The entire storyline of the series is all about understanding this seemingly absurd, unnerving “why”. The series is closest to philosophical and existential drama. It doesn’t feature red herrings or parallel timelines, and all characters, props, and plot devices appear for a reason, which makes for a refreshing break from oft-overengineered narratives of modern-day dramas. It is as close to minimalist as possible for an FX production. It is also highly stylised, beautiful, and high on artistic and technical merits.

Cinematography in Dev is an absolute delight; a technical and artistic tour de force (if Devs doesn’t get a clean sweep of the technical and art direction Emmy’s and Golden Globes, that’s it, I’m giving up on mankind). The cinematography is crisp and dreamlike at the same time, it has an incredible hyperreal feel. It is also rife in references – and as is often the case with not-so-overt ones, one wonders “is this an actual reference, or am I just inventing one?”. Night-time aerial sequences of LA seem like a clear reference to (original) Blade Runner’s visionary imagery, while daytime sequences share a degree of Sun saturation with Dredd (an underrated masterpiece Alex Garland wrote and executive-produced). The Devs unit design is homage to Vincenzo Natali’s Cube, there’s no way it’s accidental, while its brighter-than-sun lighting evokes 2007 Sunshine (written by Garland). The technical quality of the cinematography shines brightest in razor-sharp, vivid, saturated night shots – which makes one contemplate the incredible technological leap of the past 2 decades; just see one of big-budget Hollywood productions night shots from late 90’s (off the top of my head: Interview with the Vampire) to see how the technology has progressed.

Music is at times perhaps too arthouse, but it is clearly a part of the artistic vision, it’s a standout character, not a backdrop – and most of the time, it works oh so well. Once again, one can’t help but draw comparisons with Vangelis’ groundbreaking Blade Runner score, or the equally groundbreaking selection of music for 2001. On the intelligent ambient electronica side, Cristobal Tapia de Veer arresting score for Channel 4’s underrated masterpiece Utopia or Cliff Martinez’s score for Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion come to mind. Westworld’s soundtrack by Ramin Djawadi is nothing to sneeze at (especially the beautifully bittersweet Sweetwater), but it’s clearly illustration music. Devs seem closer to Brian Retizell’s avant-garde experimentations on Hannibal or subliminal ambient background to David Lynch’s 2017 Twin Peaks revival (sound-designed by David Lynch himself).

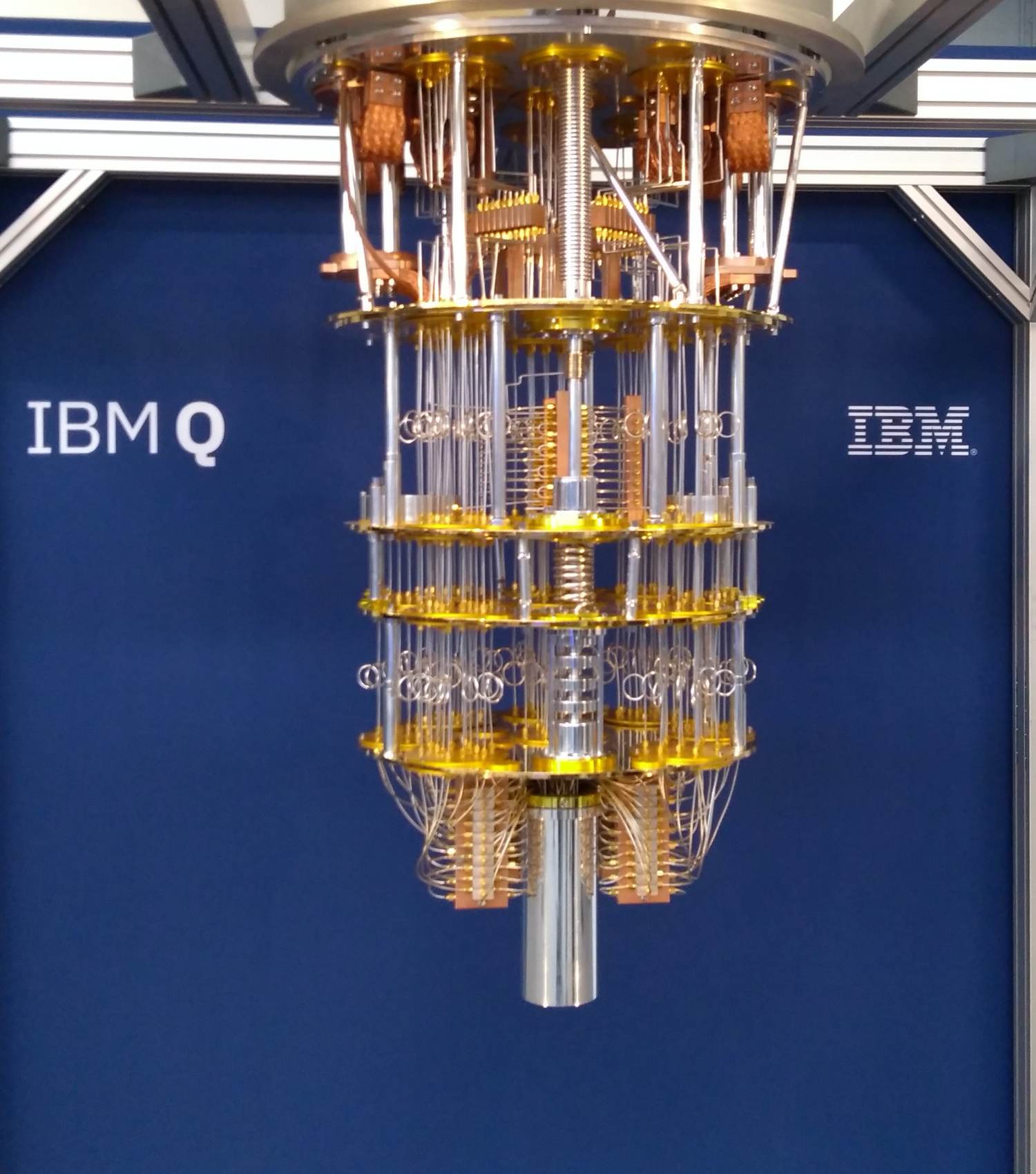

Art direction is interesting, though not at par with music or cinematography. The LA apartments of the protagonists are pretty basic (although we get the not-so-subtle message “even these basic apartments are nowadays affordable for the technocratic elite only”). The Devs’ “floating cube” is, by contrast, intentionally (?) over-the-top, while the Amaya statue towering over the campus is quite creepy, likely meant as a warning against not letting go. The way New York City was the fifth character on Sex and the City, in Devs it’s the quantum computer – which is either a carbon copy of IBM Q System One (I’ve seen it up close – a mock-up, of course, not the real, super-cooled thing), or it is actually the exact mock-up I saw (the one in Devs has some moving parts though… I’m not sure the IBM / D-Wave / Rigetti systems have any of those…). To a regular viewer it may look completely and utterly over the top, like an elongated baroque candelabra put on the floor – the weird thing is, this is exactly what a modern-day quantum computer looks like; there’s no OTT here – that’s scientific accuracy.

Art direction is interesting, though not at par with music or cinematography. The LA apartments of the protagonists are pretty basic (although we get the not-so-subtle message “even these basic apartments are nowadays affordable for the technocratic elite only”). The Devs’ “floating cube” is, by contrast, intentionally (?) over-the-top, while the Amaya statue towering over the campus is quite creepy, likely meant as a warning against not letting go. The way New York City was the fifth character on Sex and the City, in Devs it’s the quantum computer – which is either a carbon copy of IBM Q System One (I’ve seen it up close – a mock-up, of course, not the real, super-cooled thing), or it is actually the exact mock-up I saw (the one in Devs has some moving parts though… I’m not sure the IBM / D-Wave / Rigetti systems have any of those…). To a regular viewer it may look completely and utterly over the top, like an elongated baroque candelabra put on the floor – the weird thing is, this is exactly what a modern-day quantum computer looks like; there’s no OTT here – that’s scientific accuracy.

It doesn’t often happen that all elements click into place to create perfection (examples in recent years: American Horror Story season 1; Hannibal; Killing Eve, Fleabag; Twin Peaks: the Return), and unfortunately Devs aren’t quite so lucky. All its artistic and philosophical heft is undermined – painfully! – by terribly miscast leads. Some TV shows (again, using the term loosely) are cast pitch-perfect, the cast makes these shows (cases in point: Killing Eve; Hannibal; seasons 1, 2, and 5 of American Horror Story; Pose; characters of Dolores and Maeve in Westworld; Olive Kitteridge; Transparent). Given the budgets that go into modern series production, and the enormous stakes (as the shows become flagships for their platforms / networks and fight to compete in increasingly saturated marketplace) casting can make or break a show. The lead cast of Devs doesn’t quite break the show, but it’s not for the lack of trying.

Sonoya Mizuno as Lily is. a. disaster. She’s got an intriguing, androgynous appeal, but – looking at a broad and subjective spectrum of similarly intriguing actresses – she doesn’t have the sex-appeal of Tao Okamoto or Ève Salvail, the talent of Rinko Kikuchi or Saoirse Ronan, nor the charisma of Carrie-Ann Moss or Chiaki Kuriyama. We know that Alex Garland can direct its actors well (after all, Ex Machina propelled Alicia Vikander to Hollywood’s A-list; she got an Oscar a year later for The Danish Girl), so the fault is likely with Mizuno. She carries Lily with the depth of an emo teenager; her acting is flat, her emotional range is limited. I felt like crying during her crying scene, but it wasn’t tears of empathy – it was cringe-cry. Nick Offerman’s Forest takes the blank-stare dead eyes so far over the top that it’s at times almost comical. Karl Glusman – an otherwise talented actor – does Russian accent… poorly – and that’s his only contribution. Alison Pill also went over-the-top with the “brooding quantum physics genius”, doubling down on blank stare and mistaking flatness for depth – she simply isn’t convincing as a scientist. Relative newcomer Jin Ha as Jamie is the only casting bet that pays off (and just to be clear: one doesn’t need a cast of Hollywood A-listers to make a good series – just look at Succession). His character doesn’t get that much air time, but still comes across as a fully-fleshed character. He’s also refreshingly sensitive and vulnerable, which are not qualities we get to see in male protagonists very often yet. He’s nowhere near hypermasculine, he’s actually really slim-built, even slightly androgynous (androgyny is a major theme in Devs: Lily, Jamie, Lyndon – it almost seems like a message: “the intellectual / technocratic elite is above the archaic gender-binary”). Zach Grenier’s is the only other half-decent performance, with redeeming flashes of irony. No Emmy’s here. No Golden Globes.

Devs’ is a living proof that powerful vision is enough to create compelling, fascinating, binge-worthy TV. It does so without a plethora of international locations (I’m looking at you, Westworld!), an abundance of CGI (I’m still looking at you, Westworld), or elaborate purpose-built sets (my eyes still on you, Westworld). Devs has precisely one blockbusting scene (the motorway sequence with Lily and Kenton). By the very virtue of its location, it evokes Bullitt, otherwise, it is reminiscent of that motorway scene in Matrix Reloaded (obviously in a much more demure fashion – the Matrix Reloaded sequence was a stroke of cinematic genius, down to the Juno Reactor track).

As far as philosophy and technology are concerned… well, the latter is approached loosely… really loosely. It’s more of a mere notion of quantum computing than any actual science. It’s kind of the vaguest and loosest level of technological reference possible – but, judging by the reactions, it was enough to strike a chord. The reason may be two-fold: the artistic and entertainment merits of Devs, and perfect timing, as “quantum” becomes the hot new buzzword. Philosophy is more of a meditation and exploration – there are few (if any) answers or directions. It may, in fact, be one of the major strengths of Devs: it ponders and asks questions without fortune cookie-quality one-liner bits of wisdom (“There is ugliness in this world. Disarray. I choose to see beauty” – look me in the eye, Westworld…!). Westworld takes on sentience and consciousness; Devs takes on free will and determinism. It’s interesting (and impressive) how Devs gently manages to manoeuvre around the topic of religion and comes across as agnostic rather than explicitly atheistic.

Devs is a show one can describe as a “small masterpiece”. It’s slow-burning, low-key, with stunning aesthetics though no blockbusting qualities proper. The characters are not at all overtly sexy or sexual (in fact they come across somewhat asexual, even though we know they do, actually, have sex and enjoy it). There are no heists, explosions, or enormous amounts of money (money is approached a bit like sex in Devs – we know it exists, and in great amounts, but it’s almost a non-factor for the plot). One could say that not very much is happening in Devs altogether, and they wouldn’t necessarily be wrong. But somewhere between bold artistic vision, philosophical questions, stunning visuals, and outstanding music there is a true work of art: ambiguous, intriguing, thought-provoking, and truly beautiful. I’ll treasure it all the more knowing full-well how unlikely I am to see anything of remotely similar calibre anytime soon.

PS. Is it just me, or does it look like the scene of meeting Lily and Jamie was filmed on the non-existent ground floor of Exchange House in Primrose Street in London?

Royal Institution “Quantum in the City”

Sat 16-Nov-2019

On Sat 16-Nov-2019 the Royal Institution served its science-hungry patrons a real treat: a half-day quantum technologies showcase titled “Quantum in the City: the shape of things to come”. The overarching concept was to present what living in the “quantum city” of the future might look like.

It was organised with the participation of UK National Quantum Technologies Programme and ran a day after a big industry event at the QE2 Centre.

Weekend events at the RI usually differ from the standard evening lectures in that they are longer and cover one area in more depth. This one was no exception: in addition to a 1.5hr panel discussion, there was an extensive technology showcase across the 1st floor of the RI building, with no fewer than 20 exhibitors, most of them from academia or university spin-off companies.

One of the chapters from Nassim Taleb’s “skin in the game” (full disclosure: I haven’t read the whole book; I only read the abridged chapter when it appeared in my news feed on, all of the places, Facebook[1]) describes a social group he (with his usual Kanye charm) calls “Intellectual Yet Idiot”. I tick pretty much all the boxes in that description (except the “comfort of his suburban home with 2-car garage” – try “precarious comfort of his Qatari-owned 2-bed rental“), but none more than “has mentioned quantum mechanics at least twice in the past five years in conversations that had nothing to do with physics”. Guilty as charged, that’s me. The context in which I mention quantum mechanics, physics, and technologies in conversations is usually the same – I don’t understand them. I understand one or two of the basic concepts, but I still completely don’t get how with each new qubit the computing power of a quantum computer doubles, what quantum (let alone quantum-safe) encryption is, and why the observer makes all the difference (and what does “observer” even mean?! A conscious observer?!).

One of the chapters from Nassim Taleb’s “skin in the game” (full disclosure: I haven’t read the whole book; I only read the abridged chapter when it appeared in my news feed on, all of the places, Facebook[1]) describes a social group he (with his usual Kanye charm) calls “Intellectual Yet Idiot”. I tick pretty much all the boxes in that description (except the “comfort of his suburban home with 2-car garage” – try “precarious comfort of his Qatari-owned 2-bed rental“), but none more than “has mentioned quantum mechanics at least twice in the past five years in conversations that had nothing to do with physics”. Guilty as charged, that’s me. The context in which I mention quantum mechanics, physics, and technologies in conversations is usually the same – I don’t understand them. I understand one or two of the basic concepts, but I still completely don’t get how with each new qubit the computing power of a quantum computer doubles, what quantum (let alone quantum-safe) encryption is, and why the observer makes all the difference (and what does “observer” even mean?! A conscious observer?!).

Consequently, I keep going to different quantum lectures and presentations, in order to actually understand what this stuff’s about. I basically hope that if I hear it for the n-th time, something in my brain will click. It was that hope that sent me to the RI in November of 2019. Plus, I was really keen to see practical applications of quantum technology.

The discussion panel was great. The panellists were:

- Miles Padgett, Principal Investigator for the QuantIC Hub

- Kai Bongs, Director, UK Quantum Technology Hub for Sensors and Metrology (I previously attended Kai’s presentation on quantum sensors at New Scientist Live)

- Dominic O’Brien, Co-Director, NQIT (UK Quantum Technology Hub for Networked Quantum Information Technologies)

- Tim Spiller, Director, UK Quantum Technology Hub for Quantum Communications Technologies

The discussion revolved around current and future applications of quantum technologies. Like everyone, I know of quantum computers (I even saw IBM’s one during their Think!2019 event), and quantum encryption. I have a basic awareness of quantum sensors (from Kai’s talk at NS Live in 2019 or 2018) and some ambitious plans for quantum technologies-based medical imaging (“quantum doppelgangers” if I recall correctly… I heard of those during Science Museum Lates even on quantum). Paul Davies mentioned quantum biology in his own RI lecture “what is life”, as did Prof. Jim al-Khalili in some interview – but that’s about it.

Fundamentally though, my understanding was that quantum technologies are only beginning to emerge in academic and / or industrial settings. It was genuine news to me that existing technologies (chief among them semiconductors and transistors, which is basically all of modern technology and the Internet; also lasers and MRI scanners) are reliant on the effects of quantum mechanics and are referred to as “quantum 1.0”. The cutting-edge technologies emerging these days are “quantum 2.0”.

Imaging was a prominent use case for quantum technologies, across a number of fields: medical (endoscopy, brain imaging for dementia research), environmental, construction (what’s underneath the soil), industrial (seeing through dirty water or unclear air).

Quantum computing and encryption were also discussed at length. With quantum computing, we’re on the cusp of doing practically useful things at a much lower (energy and time) cost than traditional computing. (nb. the Google experiment was a test problem, not a real problem). In some use cases, quantum computing may be orders of magnitude cheaper in terms of energy consumption compared to conventional computing. In some other use cases this saving will be minimal (interesting comment – I assumed that quantum computers would generate orders-of-magnitude energy and time savings across the board). In terms of encryption, the experts at the RI repeated almost verbatim what Ian Levy from NCSC / GCHQ said at quantum computing panel at the Science Museum a few weeks prior: currently all our communications are encrypted and therefore assumed more or less safe. However, it is theoretically possible for an actor to store encrypted communications of today and decrypt them using quantum technology in the future. Work is underway to develop mathematical models for quantum-safe encryption.

There is work starting on standardization of quantum technologies to ensure their portability.

The panellists also discussed at length the research and investment landscape of quantum technologies across the UK. They noted that the UK was the first country in the world to come up with a national programme of academic + industry partnership and funding in quantum technology research. The US and their programme have (allegedly!) pretty much copied the British blueprint. To date, all distributed and committed funds are close to GBP 1bn. That’s a decent level of funding, but in part, because different groups and laboratories have been set up and funded through different sources before. If the GBP 1bn funding was to fund everything from scratch, then it might not be sufficient. Currently, a substantial part of UK quantum research funding (varies by group and programme) comes from the EU. Brexit is an obvious concern.

Separately, there is an acute talent shortage in engineering in general, and even more so in quantum technology. Big tech companies are in a strong position to compete for talent because they can offer great salaries and interesting careers.

Speaking of quantum talent, their rooms of the RI were filled with the country’s (and likely the world’s) best and brightest in the field. 20 exhibitors presented their projects, all of which were applications-based rather than pure research. Some of those were proofs of concept (PoC’s), some were prototypes, and some were in between. A handful of exhibitors stood out based on my subjective and oft-biased judgement:

- Underwater 3D imaging, ultra-thin endoscope, and a camera looking around corners (all from QuantIC: UK tech hub for quantum enhanced imaging) were all practical examples of advanced imaging applications.

- Trapped Ion Quantum Computer (University of Sussex). The technological details are a little above my paygrade, but apparently different engineering approaches towards quantum computing lend themselves differently to scaling. The researchers in Sussex use microwave technology, which differs from existing mainstream approaches and can be quite promising. I have had a soft spot and very high regard for the Sussex lab ever since I met its head, the fabulously brilliant and eccentric Winfried Hensinger when he presented at one of New Scientist Instant Expert events.

- Quantum Money (University of Cambridge) was the only project related to my line of work and a slightly exotic one even in the weird and wonderful world of quantum technologies. S-Money, as it’s called, is at the intersection of quantum theory and theory of relativity, and could enable unhackable identification as well as lag-free transacting – on Earth and beyond. And they say the finance industry lacks vision…

In summary, the RI event was nothing short of awesome. I don’t know whether I got anywhere beyond the “Intellectual yet Idiot” point on the scale of quantum expertise, but I can live with that. I learned of new applications of quantum technologies, and I met some incandescently brilliant people; couldn’t really ask for much more.

[1] Fuller disclosure: I only ever read Nassim’s „black swan”, and I consider it to be a genuinely great book. I bought “fooled by randomness” and “antifragile” with an intention of reading them some day (meaning never). Still, if I mention the titles with sufficient conviction, most people usually assume I read those end-to-end. I don’t correct them.

Leonardo at the British Library

11-Aug-2019

A museum exhibition dating back half of a millennium may not immediately seem like an organic fit in a cutting-edge finance and technology blog. However, this isn’t just any exhibition we’re talking about – this is a Leonardo da Vinci exhibition at the British Library. The quality and quantity of scientific and academic content of the works on display were orders of magnitude greater than any technology discussed throughout the rest of my blog.

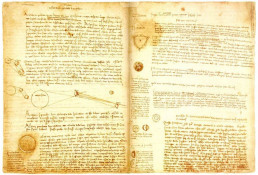

With 3 codices for the first time on display together, the exhibition makes for a riveting experience (and also a chilling one – the exhibition room is kept at 17 Centigrade in order to preserve the manuscripts). Each and every one of the pages on display (“codex” is really just a fancy term for “notebook”) presents an insight or thought that would make worthy life’s work for most non-genius folk.

Facing Leonardo’s work is an experience comparable to seeing “2001: a space odyssey” for the first time – it’s not exactly religious, not really spiritual (I don’t like this word anyway), but transcendental still. There is, of course, a huge degree of subjectivity (my mom was not exactly riveted by “2001:…”), but facing this calibre of genius up close was deeply moving. Right before my eyes, separated from me only with a thin sheet of glass, were the notes of one of the finest polymathic minds in the history of mankind.

The exhibition showcases 3 of Leonardo’s codices (out of a total of 11 his works were broken into):

- Codex Arundel: 283 sheets of notes on various subjects, including mechanics and geometry (from British Library’s own collection)

- Codex Forster: notes on a variety of scientific topics including hydraulics, weights, and geometry (from the V&A Museum in London)

- Codex Leicester: 36 sheets on a variety of topics including astronomy, geology, and the flow of water (one of the topics Leonardo seemed to have a particular fascination with). Codex Leicester is a property of Bill Gates, who purchased it in 1994 for USD 30.8 mln* (so close to a million per sheet) and allows it to be exhibited worldwide.

Leonardo’s famous mirror writing just adds to his mystique – what made him write this way? Is it just because he was left-handed? (seems a bit contrived an explanation). Fun fact: the multiplication table (up to 10×10) on one of the sheets is written left-to-right.

Even on a purely aesthetic level, Leonardo’s work is a delight. The beige sheets – almost all of them richly illustrated – have artistic values. The drawings may not all be quite Salvator Mundi-quality, but they are spectacular nonetheless. Even the handwriting itself is stylish; I mean, just look:

The realisation that Leonardo made these notes and drawings himself was pretty mindblowing in its own right. It’s almost like Leonardo was there himself.

The stylish-to-a-fault exhibition** doesn’t even present the complete contents of the 3 codices – just selected sheets, and many of these sheets contain enough to be an accomplished Renaissance academic’s life’s work. So that’s just a fraction of his scientific work, all of which is on top of 2*** of the world’s most famous paintings: the Mona Lisa and the Last Supper. To me that realisation – coming up close with it – was the most moving and transfixing experience of the entire exhibition: how did he do it? Was Leonardo just some sort of statistical inevitability (out of large enough population a supergenius polymath of his calibre simply *had to* emerge)? What did it feel like to be him? Was famously private Leonardo aware of the extent of his own genius and talent?

All these questions (and many more) were tackled by Oxford University’s Professor Martin Kemp during an accompanying event on Tue 06-Aug-2019. In an interdisciplinary talk (which lasted well over an hour but felt like a moment) he showed the audiences how to find beauty in Leonardo’s scientific work and how to find scientific accuracy in Leonardo’s art.

Prof. Kemp said that Leonardo exhibited “almost pathological attention to detail” – something I’m a big fan of myself. He also mentioned that everything Leonardo ever did (though I’m unsure whether that included paintings) was an act of analysis – “how does the mechanism work?” was apparently one of the questions driving Leonardo throughout his life and work. Professor Kemp added that Leonardo admired the perfection of the structure of things and believed that a great design had an element of inevitability; consequently, Leonardo was much more of a geometric rather than an arithmetic mind. He set himself impossible, “unfinishable” tasks (something I can relate to), was famously private (something I can’t relate to at all), but he did apparently like dirty humour (something I can relate to).

Prof. Kemp mentioned that for Leonardo science and fantasy went hand in hand. It wasn’t perhaps entirely uncommon at the time (though it would more likely have been science and religion and/or theology), but still, it seems just so naturally and organically fitting to his work, where groundbreaking science and art worked hand-in-hand.

Fun fact: Prof. Kemp is of a certain age (77 years young to be exact), yet when he was on stage discussing Leonardo, he was literally beaming with the enthusiasm and energy of someone much younger. It was quite incredible. I hope that I will one day find that one thing that will give me as much joy and fulfilment.

* Normally, I’m rather unimpressed with 8- or 9-figure sums paid for works of art (it’s pure excess to me), but I have to say, for Leonardo’s codex I’m willing to make an exception: that was money well spent.

** Fittingly, the exhibition is sponsored and styled by Pininfarina, the Italian automotive design house behind some of the world’s most stylish sports cars.

***3 If we count Salvator Mundi.

RI What is life Paul Davies

06-Feb-2019

On 05-Feb-2019 Royal Institution welcomed theoretical physicist/cosmologist/astrobiologist Paul Davies to give a lecture promoting his new book “The Demon in the Machine”.

The main themes of the lecture were “life as an informational process” and “how did life begin?”. We got a number of fascinating insights on the former, while for the latter… no, we still don’t know for sure. What was rather unique about the lecture was that it was more like an interdisciplinary discourse between some of the greatest minds in the history of modern science (Schrödinger, Crick, Maxwell, Shannon, Einstein) in which Prof. Davies was a contributor and a moderator rather than a monothematic first-person speech. And I loved it.

The lecture, with intro from esteemed Prof. Jim Al-Khalili himself, started somewhat philosophically, with Prof. Davies opening up with 2 questions-statements which would set the tone for his entire lecture:

- We can’t define what (exactly) life is

- We don’t know how it began on Earth

Professor Davies started by referencing Erwin Schrödinger’s seminal “What is Life?” and Francis Crick’s “Life Itself: Its Origin and Nature” (“An honest man, armed with all the knowledge available to us now, could only state that in some sense, the origin of life appears at the moment to be almost a miracle, so many are the conditions which would have had to have been satisfied to get it going”) and his own work in SETI Programme (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence), whose struggle is to find any life in the universe and thus (indirectly) answer the question: does life start easily? One of the current schools of thought posits that the universe should be teeming with life, and yet we have not yet found any evidence of it (Fermi’s Paradox). In the context of search for extraterrestrial life, Prof. Davies remarked that science requires a “life-meter”, which would enable it to determine not just whether a given organism is living or not (something we can do fairly well today, at least in terrestrial context), but also whether given system (e.g. planet or moon) is “on its way” to develop life, and if so, how far down the road it is.

Moving on to the main theme of his lecture, Prof. Davies remarked on the difference in ways scientists define life: physicists would talk about life in the terms of matter, force, energy, reaction rates, molecular binding etc. (“hardware speak”), biologists would define it in the sense of ribosomes, amino acids, genetic code, coding instructions in genes, transcription, gene editing and otherwise use the language of information (“software speak”).

Continuing to focus on the language of information, Prof. Davies discussed whether we can define what exactly information is and whether the biology of living systems (e.g. humans) could be mapped in the form of computer science logic. That, he said, could open up the possibility of “fixing” such issues as cancer, treating it the same way as corrupt software on a computer. He further discussed whether information as such as real, leaving the question open, but concluding scientists *do* consider information as real. From this vantage point, Prof. Davies raised the question as to how information (defined as bits and bytes) can have impact on matter, which led him to Christoph Adami’s definition: “Information is the currency of life. One definition of information is the ability to make predictions with a likelihood better than chance”. He further referenced Claude Shannon’s seminal work, in which information was defined as a reduction of uncertainty.

In the end, we didn’t get any closer to understanding how exactly life began, but some of the connections and observations Prof. Davies made between well-known and not-so-well-known theories and discoveries were truly fascinating and made for great food for thought, which is what popular science should be all about. His enthusiasm and energy shone through, while the ability to facilitate the one-man discourse among different branches of science (biology, physics, astrophysics, information theory) is – to me – what makes the difference between a good scientist and a great one.

Royal Institution: How to Change Your Mind

Mon 11-Jun-2018

The innocent and perhaps slightly dull title hid one of the more exciting RI events in recent weeks: an acclaimed author, “immersive” journalist (“when I was researching the food industry, I bought a cow”), and a UC Berkeley professor Michael Pollan was talking about his most recent book (carrying an innocent and perhaps slightly dull title “how to change your mind”…) about psychedelic substances, in particular psilocybin and LSD.

Psychedelics are currently enjoying a true (academic) renaissance. After half a century of complete obscurity (not to mention criminalisation), they are resurfacing in respected universities’ research facilities (subject to unbelievable admission rigours and control protocols, not to mention procurement), and receiving strong support from foremost academics as potential game-changers in psychiatry as well as cognitive performance enhancers. Ongoing legalisation of cannabis and shifting public perception of drugs’ harmfulness may be the catalysts.

Among the world-class academics leading the debate and the research are Prof. David Nutt of Imperial College London, who published a now-famous (re)classification of drugs based on their harmfulness in 2009, and was sacked by the Labour (sic!) government shortly thereafter, and Prof. Barbara Sahakian of Cambridge University, who – among many other things – is researching performance enhancement and “smart drugs” (you can buy her book on the topic here).

With mental illness spiralling, a prospect of single (supervised) application of LSD or psilocybin generating results comparable to *years* of traditional therapies was probably what interested the scientific community (you can watch Prof. Nutt’s presentation given at UCL’s Society for the Application of Psychedelics event in Nov-2017 here, it’s fascinating – you can hear me asking his views on legalisation towards the end). Silicon Valley – in its true “quantified self”, entrepreneurial, and somewhat quirky style – responded to “performance enhancement” (the concept of performance-enhancing “microdosing” was brought into public’s attention in a famous Sep-2016 Wired UK article you can read here; another well-known feature is the Aug-2017 article in the FT you can read here.)

Against this backdrop, any presentation on LSD and / or psilocybin is pretty much a guaranteed full house*, and this one was no exception. There were unusually many first-time-ever attendees (RI did a quick show of hands), many of which were friendly, Big Lebowski-style dudes with very long hair and an aversion to footwear. The event was MC’d by Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris, who is one of the rising stars of the younger generation of psychedelic research (you can watch him give his own presentation at UCL’s Society for the Application of Psychedelics event in Feb-2018 (a sequel to Prof. Nutt’s event) here).

Michael Pollan proved to be an experienced, engaging, and charismatic speaker, which definitely contributed to the quality of the event. In his presentation he talked about his (informal, and, by his own admission, at times not entirely legal) research and experiences of psychedelic substances, as well as experiences and views of other people who – for very different reasons – tried psychedelics.

The focus of his talk were mental health and related experiences, not on performance enhancement, which made it a little more profound (particularly the part about terminal patients confronting their fear of imminent death) than it would be otherwise. He stated, matter-of-factly, that the single guided LSD experience he had under the care of an experienced therapist (who takes huge personal risks by running such clandestine sessions) did for him what would take conventional therapy years to accomplish.

Another interesting point raised by Michael was the deep sense of closeness and togetherness with nature being the result of psychedelic experiences. I don’t recall this argument appearing in the public discourse, usually it’s just depression and performance enhancement, which made it all the more interesting.

The event went well into overtime with extended Q&A (you can hear me asking his views on legalisation towards the end) and will hopefully be uploaded to Royal Institution’s YouTube channel.

You can see upcoming RI events here, and make a small contribution here.

Royal Institution Patron’s Night: ExpeRience: A space odyssey

07-Jun-2018

June Patron’s Night event was dedicated to the legacy and themes raised in the cinematic masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The movie, due to its many exceptional qualities (stunning in-camera visuals, aesthetics, striking technological predictions (see astronauts’ using tablet computers in a movie from 1968), the rogue AI, lastly its philosophical layer) has never been entirely out of the popular discourse, but as of late it’s enjoying additional resurgence due to its rogue AI, HAL9000, appearing in each and every single conversation about AI in general, AI ethics, and AI threats.

The event was focused on some of the other themes of the movie, such as space exploration in general, space robotics, hibernation and cryonics, and the psychological aspects of space travel. RI always has great speakers, and this time was no exception.

The panel included:

- Marek Kukula, Public Astronomer at the Royal Observatory Greenwich, as the discussion host and moderator

- Calum Hervieu, space systems engineer with a focus on lunar exploration mission architectures and crew engineer for a Mars mission simulation in Hawaii.

- Professor Yang Gao, Associate Dean for Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences (FEPS) and the Professor of Space Autonomous Systems at Surrey Space Centre (SSC) and the Director of EPSRC/UKSA National Hub on Future AI & Robotics for Space (FAIR-SPACE).

- João Pedro de Magalhães, Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease, University of Liverpool and coordinator of the UK Cryonics and Cryopreservation Research Network (http://www.cryonics-research.org.uk/), which aims to advance research in cryopreservation and its applications.

- Iya Whiteley, Director of the Centre for Space Medicine at Mullard Space Science Laboratory, UCL. She is a Space Psychologist, who worked on developing Tim Peake’s astronaut selection training programmes.

If the academic cred of the guests weren’t enough, Iya’s hobby is competitive skydiving, João is an amateur stand-up comedian, and Calum recreationally runs half-marathons. Try to compete with that.

The event paid tribute to Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece and used it as a starting point for speakers’ individual short presentations. Rogue AI wasn’t one of them, and that’s a good thing, because there were enough interesting topics to discuss without it. Calum compared the scope and difficulty of lunar missions with the potential Mars mission, making it very clear how much more challenging the latter will be (if it ever happens…), and showed some concepts for human habitat on Mars (kudos to Foster+Partners for thinking about extraterrestrial markets so early in the game). Iya talked about the unique and numerous psychological challenges and considerations of a long-term (here defined as going to Mars and back, a couple of years altogether, including a minimum of 220 days in the space craft each way) space mission, some of which are difficult to relate to for ordinary people – e.g. the lack of sensation of wind or slightly varying temperature on one’s skin. Yang talked about UK’s ambition of becoming a leading player in space robotics, and the drive to enthuse the youngest generations to space exploration and robotics. João talked about hibernation and cryonics as they occur in some species of mammals and amphibians, and about ongoing research into both hibernation and cryonics of humans (mentioning Alcor, the cryonics company which first appeared on my radar in unforgettable “Future Fantastic” series hosted by Gillian Anderson many moons ago).

Presentations were followed by the usual Q&A, which was then followed by hands-on experiences, which aren’t usually the part of RI events. Attendees could see the impact of micrometeorites on space crafts, experience firsthand (literally) different rocket fuels, see what would happen to an unprotected human in the vacuum of space, or try the zero-G simulation chair. My favourite one were the rocket fuels, presented by charming and beautiful robot lady

Loved it!