United states of crypto crazy

Sat 02-Mar-2019

Some assorted reflections on cryptocurrencies a little more than a year since the peak (Dec-2017). Hindsight is always 20/20, but I never was on the crypto bandwagon (and there are timestamped records to prove it…), so I believe I have the right to a little bit of “told you so” smugness.

A number of friends and colleagues have in recent days mentioned the FCA cryptocurrency assets consultation paper, which made me reflect. That FCA is on top of fintech developments is in itself great; regulators haven’t historically always been known for being ahead of the curve, but in recent years there has been marked improvement (nb. FCA isn’t the only regulator proactively looking into cryptocurrencies – regulators in many jurisdictions including USA, German, France, China, Australia, Japan and EU (ESMA) published guidelines, consultation papers, or cautions pertaining to investing in coins and tokens).

Reading the FCA paper I recalled an article in Wired magazine (UK edition) published more or less exactly a year ago, at a time when bitcoin was only beginning the precipitous slide off its all-time peak of nearly USD 20,000 (which happened in Dec-2018), all things crypto were still the hottest topic in fintech, utilities and services were meant to become a better and less-centralized, and nothing could have possibly gone wrong. And there was plenty of money being thrown at crypto. PLEN-TY.

While the article was measured and not too hype’y, it still struck me as a little less critical than I’d expect from Wired. But that in itself is probably a reflection of the time it was written in: it was such a frenzied and insane period, even measured journalism would still reflect a little bit of that insanity, it had to (my favourite quote: “<<We had all the money we needed to build the software,>> block.one CEO Brendan Blumer told me. <<All the money that comes from the token sale will be block.one’s profit.>>” – I mean, that level of crazy puts the “AAA” CDO’s of the aughts to shame).

One thing that stood out factually in the article is that coins and tokens were referenced synonymously, while they shouldn’t be. I would have never picked up on it had it not been for a very useful session at Clifford Chance in Jun-2018, and that difference is useful to know: while the entire ecosystem is ultra-fluid (as you’d expect given that it’s entirely digital), coins are generally a medium of exchange native to given chain and do not represent any claims or assets, while tokens tend to represent claims against the issuer or some sort of rights. So it’s really not the same thing, with tokens falling quite closely under the definition of a security.

What was symbolic to me in this “what a difference a year makes” story is that *the* crypto investor extraordinaire, Brock Pierce featured in the Wired story has been a subject of a super-scathing expose by John Oliver (a part of entire episode-length scathing expose of crypto in general and bitcoin in particular) and the 2 ventures he’s been associated with are yet to revolutionise the world (I’m not saying they can’t or won’t, I’m saying that they haven’t as yet), while the other, seemingly much more measured crypto venture from the same article, Dovu, appears to still be out there, but (see above) is yet to deliver anything I would want to use.

More broadly one can’t help but notice that despite the hype, the interest, the obscene amounts of money, and genuinely innovative technology there hasn’t been a genuine game-changing disruption use case as yet; JP Morgan and its blockchain-based cross-country payment project may be one exception, the Japanese project of improving efficiency of the power grid may be another, but even those are still pilots / POC’s – definitely not verified success stories (at least not yet).

The growing prominence of ESG in investments

Fri 23-Nov-2018

The first time I heard the abbreviation “ESG” was about a decade ago at Bloomberg. It was part of a test for a specialist role in the Analytics department (the <help><help> guys). I had no idea what it meant, which meant that for a little while longer I remained a generalist. I would say that my knowledge of ESG was fairly representative of financial services at the time.

Fast forward to present day, and it’s practically a brave new world. The financial crisis is over, the AI is coming (for our jobs…), and ESG leapt from something you’d put on a glossy (non-recyclable…) annual statement as a “nice-to-have” to a “business-as-usual-goes-without-saying”.

While the term itself doesn’t have an unambiguous definition, most people (finance professionals and general public alike) seem to have a good, organic understanding thereof: broadly defined ethical, environmentally-friendly investing. The width of the spectrum will differ among individuals: some will exclude industrial animal farming, some will not; some will exclude tobacco and alcohol, some will not; many will exclude hydrocarbons; and everyone will exclude assault weapons or landmines.

Change begins with awareness. 30 years ecology was either unheard of entirely or – at best – considered a fad. Today most people have a level of environmental awareness. There have always been activists who tried to raise awareness of inconvenient truths, but it took the explosion of social media to democratize previously unwelcome content (with the obvious flipside being fake news) and gave general public the opportunity to educate themselves on the environment, sustainability, corporate governance, animal welfare etc.

The next step from awareness is action, which isn’t always easy. Consumers in the developed world are not taking very kindly to the idea of “do without” (author included). Instead, they (we…) want ever more stuff – but this time environmentally-friendly, sustainable, ethical stuff (the prodigy architect Bjarke Ingels called this philosophy “hedonistic sustainability”). With our natural-born, neoliberal, capitalist awareness, we – the consumers – know all too well that brands and corporates depend on us for their survival. It is therefore unsurprising that different shades of consumer activism erupted in recent years: we want the manufacturers of our trainers to pay their labour force in South-East Asia living wages; we want cobalt in our consumer electronics to come from conflict-free mines; we want our coffee to be Fairtrade and the milk we add to it to be organic. Alongside all this activism there is also naming and shaming: of corrupt defence contractors; of polluting coal mines; of clothing manufacturers ignoring health and safety of their seamstresses etc. etc.

Financial services (especially banks; asset managers have reputationally fared much, much better) are not always synonymous with high ethical conduct (and I’m being really charitable here…). The list of prosecuted cases, no contest settlements, and plain lack of ethics of the past decade alone will feature many of the largest players in the industry (some of them included on multiple counts). On the upside, the broad social/regulatory climate has also changed in recent years and (unabashed) greed is no longer good. One hopes that increasingly high costs of misconduct will turn out to be the best, the most effective nudge financial services could ask for.

There’s a well-known saying that no man is an island; likewise, no business is an island which can exist ignoring changes in their customers’ lifestyles, values, and preferences (at least not for very long). Consequently, financial services had to start taking notice of pressures, trends, and opportunities in the ESG space. On the banking side that comes down to good, old-fashioned lending and project finance; and when a wind or solar farm begins to look competitively (or even favourably) compared to another mine or oil rig, then financing is a matter of common business sense, with huge intangible benefits in the shape of PR, publicity, investor relations, etc. etc. On the investment side certain assetscan – over a relatively short period of time – become highly unfashionable. Big Tobacco was first, around 1980’s / 1990’s, followed in more recent years by cases of high-profile (albeit sometimes delayed, and not always full) gradual divestment from fossil fuels (Norwegian sovereign wealth fund being the best-known example).

A unique problem of ESG is the difficulty of monitoring and scoring entities and investments, especially multinationals operating in multiple markets. Glock and Kalashnikov are fairly unambiguous, but what about EADS and Boeing with their defence and missile arms? Coca-cola seems rather neutral in terms of its environmental or social impact, but what about the impact of corn (for corn syrup) plantations or contribution to the obesity epidemic? Environmental and social impacts can at least be *somewhat* quantified, but what about governance? What defines good governance? Consistently beating quarterly EPS expectations? Low employee turnover? Paying high taxes? Avoiding high taxes? That problem isn’t new, it’s just becoming increasingly prominent – and with an investment decision being binary (you either invest in something or not; you can’t half- or three quarters-invest) there is no immediate solution in sight. London Business School’s Associate Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship Ioannis Ioannou eloquently captured this conundrum during a recent sustainability event: “I’m an academic researching sustainability and governance, I can see my pension portfolio on my mobile, but I can’t see its ESG breakdown”.

There are competing analytics vendors in purely commercial space, but there is also one alternative, more “grassroot’y” approach: B Corp. Awarded by non-profit B Lab organization, B Corp certification (B standing for “beneficial”) is a quantitative (score-based) measure of given company’s accountability, sustainability, and value added to the society. As of 2018, it’s still a somewhat niche designation, but it’s highly recognised in the ESG circles. It also carries a certain cachet which organisations increasingly see as an exclusive and prestigious differentiator. Furthermore, certification is inexpensive, which means low barrier for small organisations and reduced conflict of interest for large ones (they can’t be accused of buying a B Corp certification – with the cost being low, it’s more a matter of earning than buying it). Another interesting initiative is Natural Capital Coalition, which is a business management framework taking into account both impacts and dependencies on nature. For a small organisation NCC has been really successful at signing up large corporates such as Burberry, EY, Deloitte, Credit Suisse, (part of) university of Cambridge, Nestle or – somewhat unobviously – Royal Dutch Shell (in all fairness, it’s just implementation of the framework, which may or may not inform future actions, but still, it’s a promising start).

Still, despite certain “fuzzy logic” issues, many investment decisions can be made with a degree of confidence based on company profile, its core activities, its industry, and lastly its reputation. Overall business environment also seems to be moving, fairly quickly, towards increased adoption of ESG metrics and/or principles.

Earlier this year European Commission released first proposals of EU-wide framework facilitating sustainable investment (with a proposal to develop a clear ESG taxonomy being an added bonus and proposal to link remuneration to sustainability targets a literal one) while Bank of England issued recommendation for climate risks to be factored into broader credit risk framework. On the business side, there are almost daily developments, with: UBS Asset Management recently rolling ESG data for all its funds (May-2018), Nutmeg (UK’s largest robo-advisor) doing the same in Nov-2018, or fund giant BlackRock adding 6 UCITS funds to its growing family of sustainable iShares (Oct-2018).

The push for wider adoption of ESG investments and metrics is not going without some hurdles. A number of industry bodies (Alternative Investment Management Association [AIMA], ICI Global, European Fund and Asset Management Association) pushed back on European Commission’s recommendations. The pushback focuses on competitiveness, demand and materiality and relevance of ESG disclosures. It’s a slightly peculiar situation where many firms openly advocate and push ESG agenda while trade bodies speaking on their behalf are much less enthusiastic. It may be that industry-wide consensus is not exactly here yet; it may also be that some asset managers feel that they have no choice but to be (officially) ESG advocates, while in private they do not necessarily share the sentiment quite as much. Secondly, there is no clear conclusion as to whether ESG funds outperform, underperform, or perform at par with their non-ESG counterparts; there simply isn’t enough historical data to make a conclusive and statistically meaningful determination.

My little foray into ESG ended on an unexpectedly profound and emotional note. London’s Science Museum (alongside Royal Institution and Patisserie Valerie one of my happy places) held a special one-off screening of Anote’s Ark, a documentary chronicling titular character (Anote Tong, then-president of Kiribati) crisscrossing the globe and walking the corridors of power looking for practical solutions for Kiribati and its 110,000 nationals as their small island state is being gradually submerged and deprived of fresh water by not-so-gradually rising ocean levels. Seeing this spectacularly beautiful, benign and extremely vulnerable island paradise – and, more importantly, a home to its inhabitants – literally disappearing underwater was profoundly upsetting and put all things ESG in a completely different perspective.

Mariana Mazzucato: the value of everything

British Library, 09-Jul-2018

In 2018 Mariana Mazzucato is a brand name. I first came across her in the short article Wired’s Ideas Bank, which first made me aware that everything I thought I knew about entrepreneurship and innovation was a fallacy, sold to me by corporate sector’s PR and general “hijacking of the narrative”.

The article may have been short, but the Mazzucato’s point was huge. Then there was the lunch with FT, and then the British Library event. Mazzucato’s “the value of everything” lecture was part of the series organized by the British Library and UCL, and was linked to the release of her new book (also titled “the value of everything”) which analyses how (and why) modern economies reward value extraction and rent seeking rather than genuine value creation.

And let me tell you one thing: did she deliver. With passion, confidence, and charisma Mazzucato was one of a couple of speakers whose presentations I attended in the recent weeks who proved that not only *what* you say, but also *how* you say it really, really counts (others were Ruby Wax, Izabella Kaminska and Eugenia Cheng).

The quote the presentation revolved around comes from Big Bill Haywood, who in 1929 set up first trade union, which reads “The barbarous gold barons – they did not find the gold, the did not mine the gold, they did not mill the gold, but by some weird alchemy all the gold belonged to them”.

What I found very interesting was that rather than focus on purely economic arguments (which could lead to the discussion turning academic, niche, and otherwise boring), Mazzucato, originally, provocatively, even somewhat eccentrically, stated how important storytelling and narratives are in this discussion, and how important it is to contest what is told to the public as the official version of events (Mazzucato quoted Plato’s “storytellers rule the world”; by contrast I feel tempted to quote Reagan’s “government is no the solution to our problem; government *is* the problem”; to be clear, I’m siding with Plato).

Financial services sector took the brunt of Mazzucato’s criticism, with modern politics coming a close second. The criticism of financial services ran along the standard lines of productivity and adding value, while modern day liberal politicians and public sectoras a whole were criticised for not countering the neoliberal, neoclassical corporate narrative. Pharma came third for rigging prices of medicines.

In terms of innovative thoughts and ideas, I appreciated Mazzucato joining the ranks of more and more public figures who fight to recognise user-generated data as something that has value in the economic sense, and therefore something its creators should be compensated for (e.g. in the form of UBI).

On the more iconoclastic side, I was in equal measure surprised and happy to hear Mazzucato predicting a boom (and bubble) in cleantech. I’m all for it. I could not be happier to hear it. That’s one bubble I support in full.

One thing I missed throughout the lecture was Mazzucato clearly defining “value”. She was pointing out may dysfunctional aspects of modern economy (casino banking, rigging medicine prices) and constantly referring to what does and doesn’t contribute to value, but never once had she actually defined it. The question came up in the Q&A and Mazzucato defined it fairly loosely as public purpose- / mission-driven actions, such as, for example, cleaning up the oceans. She also said that “value is created collectively”, which stands in contrast to prevailing individualist approach to entrepreneurship and life in general, so that’s definitely food for thought.

You can watch the entire lecture (87 minutes) on YouTube.

1 reason why I really, really, REALLY hate Bitcoin

1 reason why I really, *really*, REALLY hate Bitcoin

It’s 2018 and Bitcoin is all the rage. At USD 7,000 it is perhaps less of a rage than it was at USD 20,000 in Dec-2018 (although people who bought it then… well, they must be literally “all (the) rage”), but still, this price is nothing short of astonishing.

I am an enthusiast of blockchain technology, but at the same time, I know that BitCoin and blockchain are not the same thing. The latter is, in its core, a concept, a new approach of maintaining, storing, and updating ledgers and books of records. The concept requires tangible technological solutions in order to become a real-world solution, and that is happening as we speak. A number of providers (e.g. IBM, whose solution my former employer Northern Trust used in their innovative blockchain-based solution for Private Equity) offer blockchain products. BitCoin, whilst running on a blockchain network (the first, or one of the first blockchain networks in the world, and by far and large the most successful and best-known one), has no intrinsic value at all (same applies to all other “on-chain” assets, BitCoin is in no way exceptional here).

Ok, so BitCoin is a purely digital, largely unregulated*, (over)hyped, somewhat mysterious (the coin’s mysterious founder Satoshi Nakamoto certainly couldn’t predict that his decision to remain anonymous will do wonders for BitCoin’s PR and status), and first cryptocurrency of its kind. It is a speculator’s dream. Of course, for this dream to come true, BitCoin needed to catch on in the mainstream, which it did, on a scale no one could have predicted. Discussing the merits of BitCoin as an investment is like discussing the merits of a lottery ticket as an investment. Attributing to early BitCoin miners or buyers some sort of prodigious investment foresight is, frankly, ridiculous. Most of them were tech enthusiast and geeks from the depths of IT community, who were enthusiastic about the technology and were mining earliest BitCoins for fun. The second wave were speculators, who saw a developing new market and speculatively invested without caring much about the technology’s potential. There were exceptions, who seemed to be genuine BitCoin believers (most famous among them being the Winklevoss twins**), but basically, it was a speculators’ market from Day 2 onwards. And then, with some serendipity and luck, this happened:

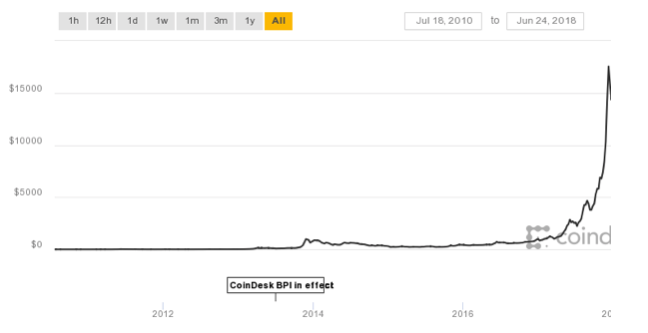

Chart source: Coindesk.com

Chart source: Coindesk.com

NB. The peak is actually slightly understated here, BitCoin got very close to USD 20,000 on some exchanges in Dec-2018.

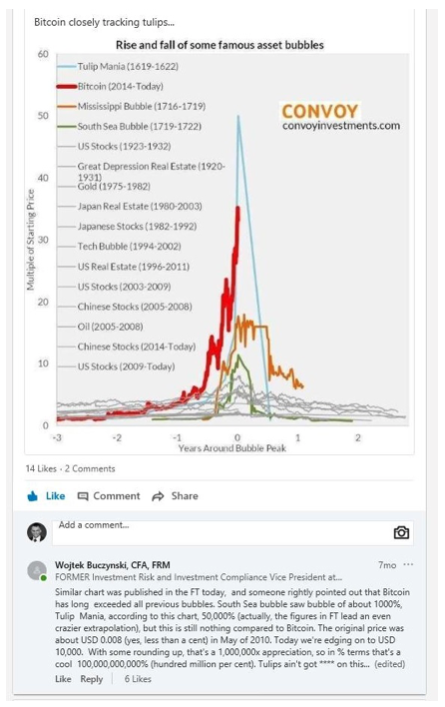

Fortunes were made, “get rich quick” seminars abounded, evangelists of “it can only go up” appeared and quickly became truly fanatical. All the conditions for an asset bubble / mania were met, and then exceeded. I’m modestly proud to be able to prove that I already held these views when BitCoin was reaching new heights on a daily, a while before its Dec-2018 peak, as can be evidenced by this LinkedIn post from late Nov-2017:

AND THAT’S FINE.

AND THAT’S FINE.

Anyone can do with their money what they see fit, and if it’s speculative BitCoin investment, so be it.****

What is decidedly *not* fine is the exponentially growing environmental cost of BitCoin mining as a result of mining operations’ energy use. The first big news (which took a lot of people, author included) by surprise was that BitCoin mining used more energy per annum than all of Ecuador. Then Ireland. Then Denmark. Then Ireland. Then more than 159 countries in the world.*****

That’s a hell of a lot of energy.

And still, this wouldn’t cause the author so much grief (no grief in fact, perhaps even some jubilation) if that energy was put to good use. Currently the algorithms miners need to crunch in order to demonstrate their proof of work and earn BitCoin transaction validation rights (which is how BitCoins are generated) don’t mean anything. They’re just complicated equations consuming enormous amounts of electricity and computing power. Which, in author’s view, shows that the closest to what can be a tangible, real-world classification of BitCoin is that of pollution derivative (which also makes BitCoin a self-referential instrument, because it’s pollution generated in the process of BitCoin mining). BitCoin is pollution, it’s as simple as that. If only, instead of solving explicitly pointless equations, the credits were given for participation in science- or healthcare-related distributed computing projects such as:

- LHC@Home: Aiding CERN’s particle research

- Einstein@Home: Detection of gravitational waves (actually, they were detected in 2015 and won a Nobel prize in 2017, but the project is still running, and my laptop is contributing to it because I saw a popular science programme about LIGO in Louisiana, I thought it was awesome, and that was that; proudly contributing my CPU power since 2016).

- SETI@Home: The original @Home project aiding search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

- Or, if they’d prefer something more human-centric, there’s always Folding@Home, whose research helps in a fight with cancer, Zika, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and several other serious, often terminal conditions.

If the computing and electric power currently used to mine BitCoin were repurposed for the purpose of science, one can only imagine how many advances we’d have achieved by now. A thorough understanding of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s? Advanced climate modelling? Better understanding of the human brain? A detailed 3D model of the Milky Way? Advanced mathematics? Particle physics? Nuclear fusion?

It truly boggles the mind how much good could be accomplished out of something that today goes to complete, asset-bubble-fuelled, waste. We’d get so much closer to Stage I on the Kardashev scale on this alone.

And yet this is no happening, and it doesn’t look like it will. One can blame the BitCoin foundation for this as the people who set the rules for the BitCoin network (which is a mess), but even they can’t be blamed in full. The real parties to blame are the usual suspects: greed, short-sightedness, bandwagon effect, etc.

And this is why I hate BitCoin.

PS. This article is not moaning of a sore loser. I neither lost money on BitCoin nor missed on it out altogether. In the brief period when I was allowed to trade it (i.e. approx. 2 months between jobs), I made approx. 13% by betting on BitCoin’s downfall and volatility. 13% is a negligible profit by BitCoin standards, but by real world standards it’s not too shabby. So I haven’t missed out, and if I still could hold my positions, I’d have made much more than 13% by holding on to my all-short position. Still, on risk-return basis, this wasn’t a very good return.

* That’s perhaps not entirely true: South Korea flirted with the idea of banning cryptocurrency trading via anonymised accounts (mostly concerned about money laundering and concerns over its citizens gambling away their savings) around Jan-2018 before deciding not to proceed; China banned ICO’s and cryptocurrency trading in full in Jan-2018; India introduced a similar ban in Feb-2018

BUT…

- This is an incredibly fast-moving market, and any government / regulatory restrictions may be lifted just as quickly as they were applied

- For purely digital assets (which they are) the restrictions can be easily bypassed: VPN access to a network of a country that doesn’t prohibit crypto trading, a TOR browser, an exchange permitting anonymised accounts. Obviously, these activities will constitute a breach of the law, but at the same time, they will be fairly difficult to detect.

** The author doesn’t usually feel sorry for people who got USD 65mln as a court payout, but he couldn’t help but feel that they walked from the Facebook affair somewhat shortchanged. Therefore their early investment in BitCoin (some would say lucky, but they appeared to be solid believers back in 2013, so they deserve some kudos) and its subsequent exorbitant rise in value (100,000 coins worth, at the Dec-2018 peak, close to USD 2bn) was welcome. As a reminder, their idea for a BitCoin ETF (which isn’t that much different to existing BitCoin futures and their offshoots on financial spread betting platforms) was met with reactions best captured in this ZeroHedge article***.

*** The author doesn’t like or read ZH since approx. 2014, when it was becoming more political and less financial, but in its heyday it had one hell of news and commentary.

**** The author believes there will be a lot of tears, buyers’ remorse, and fortunes and savings lost sooner rather than later.

***** The Digiconomist blog has an ongoing analysis of BitCoin’s energy consumption. Another good analysis can be found on PowerCompare.